The Destabilizing Danger of

Cyberattacks on Missile Systems

‘Left-of-launch’ attacks that aim to disable enemy missile systems may increase the chance of them being used, not least because the systems are so vulnerable.

"Hay que trabajar, trabajar...Trabajar y ayudar al que lo merece. Trabajar aunque a veces piense uno que realiza un esfuerzo inútil. Trabajar como una forma de protesta. Porque el impulso de uno sería gritar todos los días al despertar en un mundo lleno de injusticias y miserias de todo orden: ¡Protesto! ¡Protesto! ¡Protesto!" (Federico Garcia Lorca)

Oración por Trump y las Fuerzas Armadas en el Despacho Oval.

— Argemino Barro (@Argemino) March 5, 2026

El año pasado Trump creó la Oficina de la Fe y la colocó en el Ala Oeste de la Casa Blanca. La lidera Paula White-Cain y otros predicadores alineados con la agenda del presidente.pic.twitter.com/88eo00gIHd

Rifi rafe entre Pablo Iglesias y Jesús Cintora. Se han dicho muchas cosas a la cara. pic.twitter.com/Ida4TRMWN4

— Jesús Quintero 🇵🇸 (@jesusquinbu) October 24, 2025

Earlier this morning, on President Trump's orders, I directed a lethal, kinetic strike on a narco-trafficking vessel affiliated with Designated Terrorist Organizations in the USSOUTHCOM area of responsibility. Four male narco-terrorists aboard the vessel were killed in the… pic.twitter.com/QpNPljFcGn

— Secretary of War Pete Hegseth (@SecWar) October 3, 2025

חשיפה : כך עזה תראה בעתיד.

— גילה גמליאל - Gila Gamliel (@GilaGamliel) July 22, 2025

הגירת עזתים מרצון רק עם טראמפ ונתניהו.

זה אנחנו או - הם !

לינק לתוכנית ההגירה מרצון מעזה שהגשתי לקבינט בשבוע הראשון למלחמת 'חרבות ברזל' 13.10.23 בתגובה הראשונה. pic.twitter.com/kdPXcONmQl

A footage reveals the Israeli army torturing Palestinian prisoners in Megiddo prison, located in Israel ⤵️ pic.twitter.com/NgluPirncc

— Anadolu English (@anadoluagency) September 6, 2024

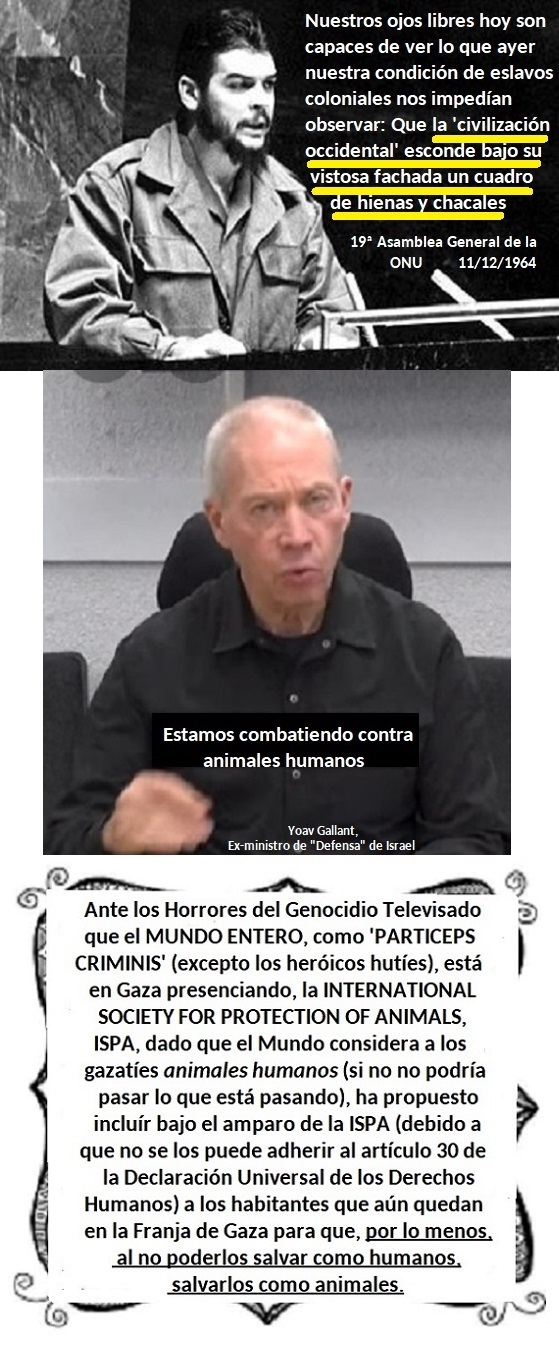

ESTO ES LO QUE NOS DA MIEDO DE LA DICTADURA CAPITALISTA Y ES LO QUE NOS QUITA TODAS LAS ESPERANZAS: SU LADO ENFERMO, SU EXACERBANTE TERATOLOGIA QUE LE HACE PONER A MARX Y A LENIN UNA "BATA BLANCA" MAS ALLA DEL CONSABIDO MOTOR DE LA "LUCHA DE CLASES" QUE SE VE SOBRE-PASADO POR EL "DELIRIUM TREMENS" DE UNA PATOLOGIA QUE, REPETIMOS, NOS HACE PERDER LA CONFIANZA EN EL "MONO VESTIDO, SEXOMANO Y DESORIENTADO"...NO DE OTRA FORMA NOS PODEMOS EXPLICAR ESTE VÍDEO. (LO TANTAS VECES DICHO: SOMOS UNA "ANOMALIA" EN EL COSMOS (Erich Fromm)President of the United States posts video of him taking over Gaza with his statue for worship, dollars raining, Trump Gaza as centrepiece as he & Netanyahu chill at the beach. Ethnic cleansing rebranded as a real estate deal. Colonialist White Supremacist Zionism. Pure Evil. pic.twitter.com/uJIk7FLykE

— Dr Shola Mos-Shogbamimu (@SholaMos1) February 26, 2025

DISCULPEN LAS MOLESTIAS QUE PUDIERA HABER CAUSADO EL VIDEOEarlier this dawn, more than 100 Palestinians were killed and dozens injured as Israeli missiles destroyed al-Tabi’n school in al-Daraj area east of Gaza city, a place which only houses displaced families.

— TIMES OF GAZA (@Timesofgaza) August 10, 2024

Among the dead are, mostly, women, children and elderly, and the toll is… pic.twitter.com/MuVefmcGdD

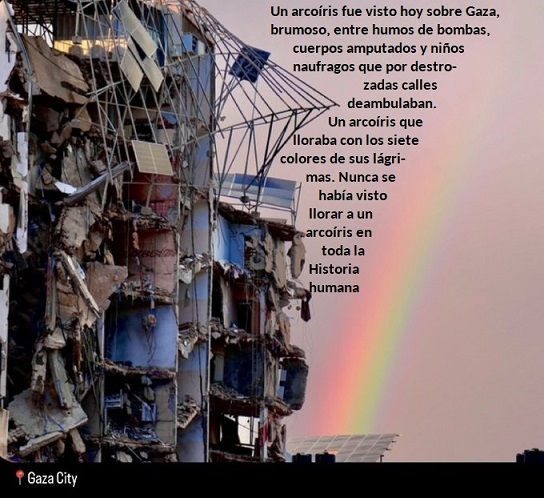

Gaza pic.twitter.com/9VkDBC0nQd

— Muhammad Smiry 🇵🇸 (@MuhammadSmiry) June 17, 2024

"We're all fine mama, we're all fine... I want to stay with mama... I want to go with mama and baba!"

— TIMES OF GAZA (@Timesofgaza) February 26, 2024

Footage from the aftermath of an Israeli airstrike on a family home in Rafah pic.twitter.com/XGlL5BYLTt

This is heartbreaking ❤️🩹 it will break you & make you want to cry.

— Alpha100 (@100_alpha) February 13, 2024

Amazing she is still smiling; despite cold & hunger this little #Angel shows how brave & strong she is.

Where is Humanity? Where is Justice?

Shame on World Leaders; Silence is Complicity!#FreePalestine #SaveGaza pic.twitter.com/bmKYAEjCdG

‘Left-of-launch’ attacks that aim to disable enemy missile systems may increase the chance of them being used, not least because the systems are so vulnerable.

"El Golpe fue diseñado para tomar medidas inmediatas que garantizaran la suspensión de los derechos y libertades fundamentales que se ganaron (al menos en nombre) después de muchos siglos de lucha...y lo hicieron de forma perfecta: para que las gentes lo aceptaran por Miedo. Esta es la razón por la cúal la idea de la pandemia del virus conocido es bastante inteligente"

https://www.globalresearch.ca/elite-covid-19-coup-against-terrified-humanity-resisting-powerfully/5709479