A principios de la década de 1970, Fons Elders condujo el International Philosophers Project, una serie de debates entre los filósofos más destacados de la época: Alfred Ayer y Arne Naess, John Eccles y Karl Popper, Leszek Kolakowski y Henri Lefebvre. Uno de los debates más resonantes del proyecto fue el que sostuvieron Noam Chomsky y Michel Foucault, celebrado en la Universidad de Amsterdam en 1971 y transmitido por la televisión holandesa.

So it is in the name of a purer justice that you criticise the functioning of justice ?

There is an important question for us here. It is true that in all social struggles, there is a question of "justice".

CHOMSKY:

Yeah, but surely you believe that your role in the war is a just role, that you are fighting a just war, to bring in a concept from another domain. And that, I think, is important. If you thought that you were fighting an unjust war, you couldn't follow that line of reasoning.

I would like to slightly reformulate what you said. It seems to me that the difference isn't between legality and ideal justice; it's rather between legality and better justice.

I would agree that we are certainly in no position to create a system of ideal justice, just as we are in no position to create an ideal society in our minds.

We don't know enough and we're too limited and too biased and all sorts of other things. But we are in a position-and we must act as sensitive and responsible human beings in that position to imagine and move towards the creation of a better society and also a better system of justice.

Now this better system will certainly have its defects. But if one compares the better system with the existing system, without being confused into thinking that our better system is the ideal system, we can then argue, I think, as follows :

The concept of legality and the concept of justice are not identical; they're not entirely distinct either. Insofar as legality incorporates justice in this sense of better justice, referring to a better society, then we should follow and obey the law, and force the state to obey the law and force the great corporations to obey the law, and force the police to obey the law, if we have the power to do so.

Of course, in those areas where the legal system happens to represent not better justice, but rather the techniques of oppression that have been codified in a particular autocratic system, well, then a reasonable human being should disregard and oppose them, at least in principle; he may not, for some reason, do it in fact.

FOUCAULT:

But I would merely like to reply to your first sentence, in which you said that if you didn't consider the war you make against the police to be just, you wouldn't make it.

I would like to reply to you in terms of Spinoza and say that the proletariat doesn't wage war against the ruling class because it considers such a war to be just. The proletariat makes war with the ruling class because, for the first time in history, it wants to take power. And because it will overthrow the power of the ruling class it considers such a war to be just.

Yeah, I don't agree.

I don't, personally, agree with that.For example, if I could convince myself that attainment of power by the proletariat would lead to a terrorist police state, in which freedom and dignity and decent human relations would be destroyed, then I wouldn't want the proletariat to take power.

In fact the only reason for wanting any such thing, I believe, is because one thinks, rightly or wrongly, that some fundamental human values will be achieved by that transfer of power.

When the proletariat takes power, it may be quite possible that the proletariat will exert towards the classes over which it has just triumphed, a violent, dictatorial and even bloody power. I can't see what objection one could make to this.

But if you ask me what would be the case if the proletariat exerted bloody, tyrannical and unjust power towards itself, then I would say that this could only occur if the proletariat hadn't really taken power, but that a class outside the proletariat, a group of people inside the proletariat, a bureaucracy or petit bourgeois elements had taken power.

Well, I'm not at all satisfied with that theory of revolution for a lot of reasons, historical and others. But even if one were to accept it for the sake of argument, still that theory maintains that it is proper for the proletariat to take power and exercise it in a violent and bloody and unjust fashion, because it is claimed, and in my opinion falsely, that that will lead to a more just society, in which the state will wither away, in which the proletariat will be a universal class and so on and so forth.

If it weren't for that future justification, the concept of a violent and bloody dictatorship of the proletariat would certainly be unjust. Now this is another issue, but I'm very sceptical about the idea of a violent and bloody dictatorship of the proletariat, especially when expressed by self-appointed representatives of a vanguard party, who, we have enough historical experience to know and might have predicted in advance, will simply be the new rulers over this society.

Yes, but I haven't been talking about the power of the proletariat, which in itself would be an unjust power; you are right in saying that this would obviously be too easy. I would like to say that the power of the proletariat could, in a certain period, imply violence and a prolonged war against a social class over which its triumph or victory was not yet totally assured.

Well, look, I'm not saying there is an absolute.. . For example, I am not a committed pacifist. I would not hold that it is under all imaginable circumstances wrong to use violence, even though use of violence is in some sense unjust. I believe that one has to estimate relative justices.

But the use of violence and the creation of some degree of injustice can only be justified on the basis of the claim and the assessment-which always ought to be undertaken very, very seriously and with a good deal of scepticism that this violence is being exercised because a more just result is going to be achieved. If it does not have such a grounding, it is really totally immoral, in my opinion.

I don't think that as far as the aim which the proletariat proposes for itself in leading a class struggle is concerned, it would be sufficient to say that it is in itself a greater justice. What the proletariat will achieve by expelling the class which is at present in power and by taking over power itself, is precisely the suppression of the power of class in general.

POSTED BY AD HUMANITATEM

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

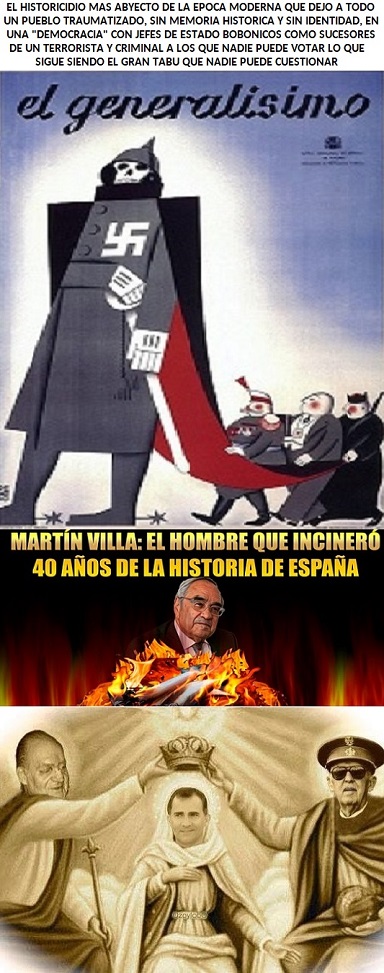

La Justicia Popular se hace tema complejo cuándo se quiere valorar y enjuiciar sin poner escenarios concretos, pero una vez delimitados éstos, todo se hace claro y manifiesto.

Seamos precisos y no nos andemos por las ramas: la justicia popular, cuando mandan los intereses colectivos sobre los privados en una economía estatal planificada para mantener la distribución de las riquezas sobre éste status con las correspondientes instituciones, sistema judicial, tribunales y demás aparatos del Estado...es el Pecado Mortal contra el que el Poder y sus LACAYOS levantará siempre sus brazos armados para eliminarlo. Para muestra un botón:

Michel Foucault: "Sobre la justicia popular. Debate con los maos".«Sur la justice populaire. Debat ayee les maos», en rey. Les Temps Modernes, n° 310 bis, 1972. Págs. 335-366.

http://www.pensamientopenal.com.ar/system/files/2014/12/doctrina39670.pdf