¿Qué debo hacer?,

¿Qué puedo esperar?,

y, por ultimo, la esencial:

¿Qué es el hombre?

“A la primera pregunta" --decía el metodico filosofo-- "responde la metafísica, a la segunda la moral, a la tercera la religión y a la cuarta la antropología [...] En el fondo, todas estas disciplinas se podrían refundir en la antropología, porque las tres primeras cuestiones revierten en la última”.

¿Qué ha hecho la antropologia en respodernos a esa última pregunta?

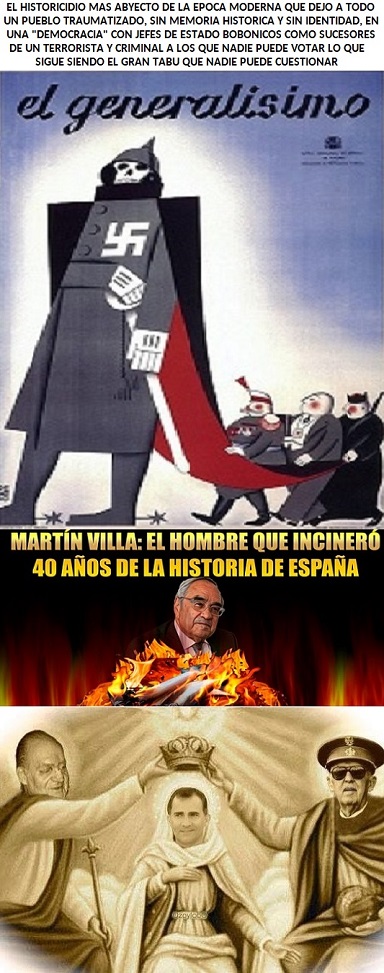

Básicamente, aparte de todos sus descubrimientos técninos morfológicos, anatómicos, recolección de fosiles, fechas y antiguedad, seguimos en pañales y el tabú sigue siendo el de siempre: el hombre mismo.

No sabemos el por que a nadie, o a muy pocos, se le ocurre la idea de que para contestar a la pregunta de marras, es decir, para tratar de conocer que es el hombre de "per se", no vean la necesidad de ver, de estudiar al hombre separado de supropia especie, sin contacto cultural con sus miembros para observar con que bagaje "natural" llega al mundo.

Demos aqui éste indespensable paso cognoscitivo al respecto.

Wolf Children

and the

Problem of Human Nature

Lucien Malson

The Wild Boy of Aveyron

Wolf Children

and the

Problem of Human Nature

Why this theory should have caused such a scandal when it was advanced by the existentialists a few years ago is still not clear since it is now the explicit assumption of all the main currents of contemporary thought.

Behaviourists deny that 'mental characteristics or intellectual skills and capacities can be inherited'.

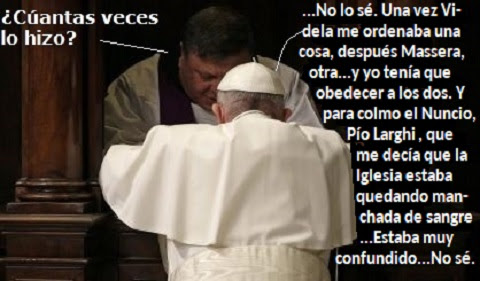

Marxism recognizes that 'man at birth is the least capable of all creatures and that this is 'the pre-condition of his further progress', in the words of Lagache, confirms that 'there is nothing in human beings to suggest the presence of instincts with their own patterns of development'.

That current which combines elements from both Marxism and psychoaoalysis --culturalism--dispels any remaining doubts on this issue by revealing just how much the individual owes to the environment in the construction of his personality.

The learning of skills by imitation among the higher animals, and the influence of group suggestion, among the lower animals which live in a sort of permanent hypnosis, are now recognized as evidence of the important part which the environment plays in the shaping of the instincts.

But the instincts are still treated nevertheless as a sort of 'a priori of the species' whose directions each member has to follow, even when separated prematurely from the group.

The behaviour of animals is to this extent based on something like a nature. Complete isolation of the human child, on the other hand, reveals the absence of these dependable a priori, of adaptive schemata the species.

Children deprived too early of all social contact --those known as feral or 'wolf children'-- become so stunted in their solitude that their behaviour comes to resemble that of the lower animals. Rather than a state of nature in which one can detect

a rudimentary "homo sapiens" or "homo faber" one discovers instead a condition of such abnormality that to understand it one needs not psychology, but teratology.

The fact is that human behaviour does not depend on heredity to the same extent as animal behaviour. The system of biological needs and functions carried by the genotype and passed on to man at birth relates him to all other living creatures rather than defines him as specifically human, and it is this very absence of predetermined characteristics which means that man's possibilities are unlimited.

(.....)

Before his encounter with others man is nothing but a notionaal quantity as thin and insubstancial as mist. To acquire his substance, he requires a milieu, the ppresence of others.

(...)

Nevertheless of this much we can be certain: there exists today a being which, unlike everything else in the world, does not appear at birth as a 'prefabricated system' which has still to be constructed and has everything to learn.

(...)

The problem of human nature is the problem of psychological heredity. For though it is perfectly plain that man can inherit biological characteristics, when one examines the area in which he displays his peculiarly human qualities...it is extremely doubtful whether there is anyting here which is genetically transmitted.

(...)

The critique of individual psychological heredity has been pursued in two different but related fields: the sociology of the family and the study of twins. The critique of generic psychological heredety has also been mounted on two fronts: cultural anthropology and the analysis of children in complete isolation, it is this last area which is the least well-known and the one for which the available source material is mostly German or Anglo-Saxon. It is on this that we will concentrate.

But first we must summarize certain basic findings which will help to clarify and lend support to the ideas which will emerge from our own study. We will use the current evidence on mental heredity as additional proof. It points towards our own conclusion that the search for human nature among 'wild' children has always proved fruitless precisely because human nature can appear only when human existence has entered the social context."

(Paginas 9-10-11-12)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Hemos llegado al epicentro del "terremoto" que crea la pregunta de preguntas, ¿qué es el hombre?.

Para empezar a responder con un mínimo adecuado de consistencia y substancialidad objetiva a tal interrogante, ahora tenemos que dar un primer paso dialéctico muy simple, muy obvio:

si se quiere saber lo qué es el hombre de "per se", en si mismo, hay que separarlo del hombre, del conglomerado cultural que nos forma, para averiguar, realmente con que bagaje inmanente llegamos al mundo antes de que el transfondo cultural de la especie nos forme a su imagen y semejanza como 'sapiens' ; ésta es la unica forma de averiguar "qué somos", en si mismo, en nuestro coro ancestral.

De no hacerse asi, siguiendo ésta metodologia, y tratar de contestar a la pregunta de marras una vez que el nuevo ser humano ha sido manufacturado bajo la fábrica cultural de su especie, es lo mismo que responder a qué es algo, en su materia original --porque creemos que la pregunta ¿qué es el hombre? es ésto-- 'a posteriori' de que ha sido construido y modelado según unos patrones predeterminados y establecidos que le daran a ese algo que queremos estudiar unas características que ya no pertenecen a lo intacto de esa materia original por la que nos tenemos que preguntar.

Entonces, el primer paso ya es evidente: el hombre hace al hombre. El hombre --que no el 'homo' del proceso de la natural recapitulación que nos enseña la embriológia--, el "sapiens", es un producto absolutamente cultural, artificial.

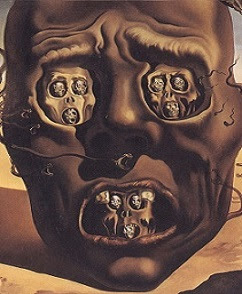

El hombre, eso si, aparece con un contenedor, con un depósito de 1.500 cm3, que, de no llenarse con las necesidades culturales y sobrevivenciales del grupo, se convierte, no ya en un animal inadaptado, sino en un caso TERATOLOGICO, es decir: una criatura sin el subconsciente de su especie, pues hasta esto debe ser aprendido e infundido:

"Children deprived too early of all social contact --those known as feral or 'wolf children'-- become so stunted in their solitude that their behaviour comes to resemble that of the lower animals. Rather than a state of nature in which one can detect a rudimentary "homo sapiens" or "homo faber" one discovers instead a condition of such abnormality that to understand it one needs not psychology, but teratology."

Pongamos atencion:

Ni "homo sapiens",

ni "homo faber",

ni "homo erectus",

ni un caso "psicológico":

somos, materia original, un caso teratologico,

sin definicion,

deforme,

sin encuadre,

deforme,

inclasificable...

y lo principial y mas significativo:

sin lengua, sin comunicación: una especie de sordo-mudos, asi aparecemos en el mundo al desnudo, genesica materia original de lo que somos. Porque sino se aprende a hablar en la primara parte de nuestra vidas, nunca mas nos podremos comunicar con los demas lnguisticamente, porque, evidentemente, nuestra habla comunicativa n es algo natural, sino artificial, aprendido.

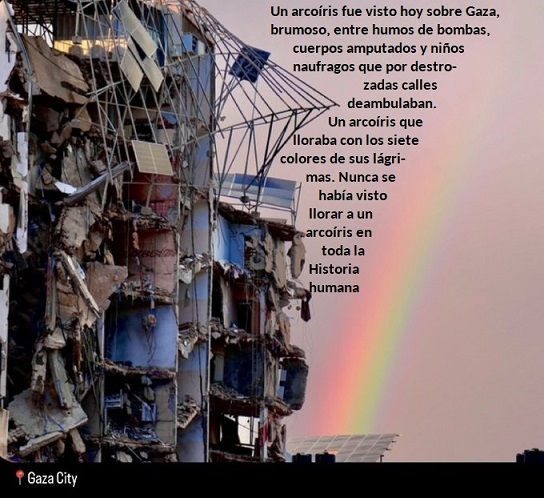

Ninguna criatura conocida viene al mundo de esta manera.

Y si vieramos una nos asustariamos, pero en nosotros mismos nada nos asusta...No nos queremos asustar de nosotros mismos.

Es evidente.

Ahora vemos claro que la pregunta de marras no ha sido aun contestada porque su respuesta, consecuentemen, también nos asustarían.

La Naturaleza no ha creado al hombre: el hombre se ha creado a si mismo. El hombre no es la consecuencia de una evolucion natural por la sencilla razon de que, a diferencia de todas las demas criaturas que pueblan con nosotros el planeta,

Linneo, que fue el primero en sacar al hombre de su "divina gracia" y ponerlo en su lugar, si tiene ésto en cuenta y en su taxonomia biologica esta éste ser, que, si al nacer se lo saca del cuidado de los suyos, se convierte en algo unico en toda la naturaleza: un caso teratologico.

Linneo lo llamo "Homo ferus", realmente, el genuino nombre del "Homo sapiens sapiens" en su estado natural: al nacer: sin contactos culturales, al desnudo, en limpio.

Veamos a estos "Homis feris" en su historia.

Pasemos a la Segunda Parte.

http://sisifocansado.blogspot.com/2011/06/que-es-el-homo-sapiens-sapiens.html