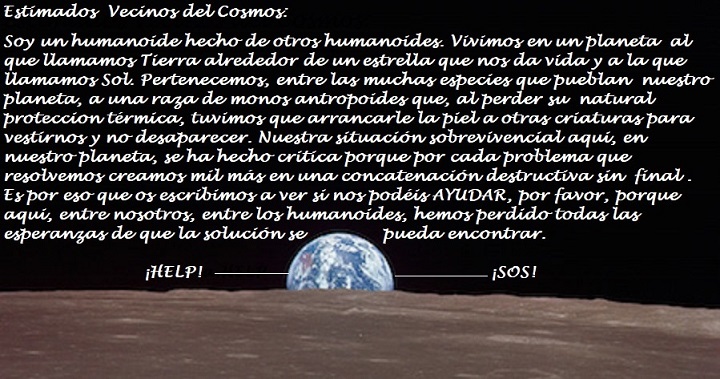

AN OPEN LETTER TO THE KING BOURBON,

HEAD OF THE SPANISH STATE,

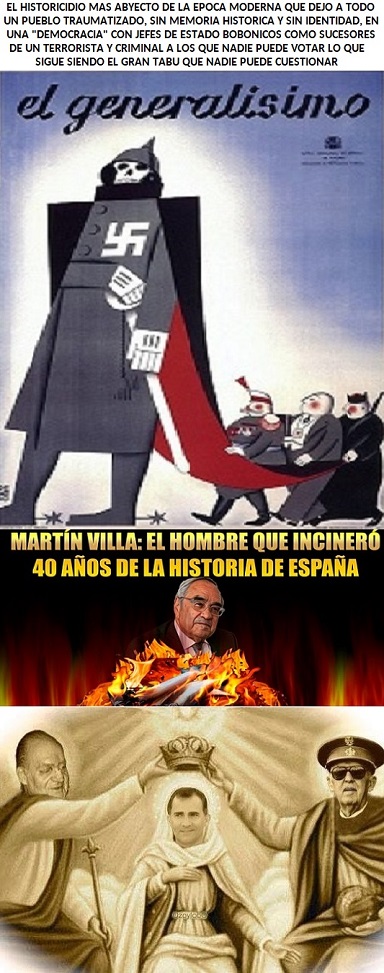

BY THE WILL OF THE GENERALISIMO FRANCO,

EX-CAUDILLO OF SPAIN "BY THE GRACE OF GOD"

('THE HITLER OF SPAIN' FOR FORTY YEARS).

Majesty, this letter is to remind you that,

on January 21, 2010, will be the 217th aniversary

of the execution, under the guillotine,

of your predecessor Louis XVI,

and maybe you are interested

to know the history of what took place on that day.

"Saint-Just introduced Rousseau's ideas into the pages of history. At the King's trial, the essential part of his arguments consisted in saying that the King is not inviolable and should be judged by the Assembly and not by a special tribunal.

His arguments he owed to Rousseau. A tribunal cannot be the judge between the king and the sovereign people. The general will cannot be cited before ordinary judges. It is above everything.

The inviolability and the transcendence of the general will are thus proclaimed. We know that the predominant theme of the trial was the inviolability of the royal person. The struggle between grace and justice finds its most provocative illustration in 1793 when two different conceptions of transcendence meet in mortal combat.

Moreover, Saint-Just is perfectly aware of how very much is at stake: "The spirit in which the King is judged will be the same as the spirit in which the Republic is established."

Saint-Just's famous speech has, therefore, all the earmarks of a theological treatise. "Louis, the stranger in our midst," is the thesis of this youthful prosecutor. If a contract, either civil or natural, could still bind the king and his people, there would be a mutual obligation; the will of the people could not set itself up as absolute judge to pronounce absolute judgment. Therefore it is necessary to prove that no agreement binds the people and the king.

In order to prove that the people are themselves the embodiment of eternal truth it is necessary to demonstrate that royalty is the embodiment of eternal crime. Saint-Just, therefore, postulates that every king , is a rebel or a usurper. He is a rebel against the people whose absolute sovereignty he usurps. Monarchy is not a king, "it is crime". Not a crime, but crime itself, says Saint-Just. In other words: absolute profanation. "No one can rule innocently." Eyery king is guilty, because any man who wants to be a king is automatically on the side of death.

Saint-Just says exactly the same thing when he proceeds to demonstrate that the sovereignty of the people is a "Sacred matter."

Citizens are inviolable and sacred and can be constrained only by the law, which is an expression of their common will. Louis alone does not benefit by this particular inviolability or by the assistance of the law, for he is placed outside the Contrat (the 'Social Contrat' of Rousseau)

He is not part of the general will; on the contary, by his very existence he is a blasphemer against this all-powerful will. He is not a "citizen", which is the only way of participating in the new divine dispensation...Therefore, he should be judged and nothing more.

But who will interpret the will of the people and pronounce judgment? The Assembly, which by its origin has retained the right to administer this will, and which participates as an inspired council in the new divinity. Should the people be asked to ratify the judgment? We know that the efforts of the monarchists in the Assembly were finally concentrated on this point. In this way the life of the King could be rescued from the logic of the bourgeois jurists and at least entrusted to the spontaneous emotions and compassion of the people.

But here again he pushes his logic to its extremes and makes use of the conflict, created by Rousseau, between the general will and the will of all. Even though the will of all would pardon, the general will cannot do so. Even the people cannot efface the crime of tyranny.

The crime of the king is, at the same time, a sin against the ultimate nature of things. A crime is committed, then is pardoned, punished or forgotten. But the crime of royalty is permanent; it is inextricably bound to the person of the king, to his very existence. Christ Himself, though He can forgive sinners, cannot absolve false gods. They must disappear or conquer. If the people forgive today, they will find the crime intac tomorrow, even though the criminal sleeps peacefully in prison. Therefore there is only one solution:

"To avenge the murder of the people by the death of the King"

The only purpose of Saint-Just's speech is, once and for all to block every egress for the King except the one leading to the scaffold. If, in fact, the premises of 'The Social Contract' are accepted, this is logically inevitable...Theocracy was attacked in principle in 1789 and killed in its incarnation in 1793.

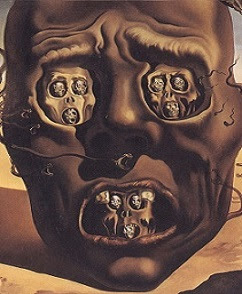

On January 21, 1793, with the murder of the King-priest, was consummated what has significantly been called the passion of Louis XVI...But the fact remains that, by its consequences, the condemnation of the King is at the crux ot our contemporary history. It symboljzes the secularization of our history and the disincarnation of the Christian God. Up to now God played a part in history through the medium of the kings.. But His representative in history has been killed, for there is not longer a King. Therefore there is nothing but a semblance of God, relegate to the heaven of principles . (This will become the God of Kant, Jacobi and Fitche)

Louis appointed by divine right, and that with him, in a certain manner, died temporal Christianity. To emphasize this sacred bond, his confessor sustained him, in his moment of weakness, by reminding him of his "resemblance" to the God of Sorrows. And Louis XVI recovers himself and speaks in the language of this God: "I shall drink", he says, "the cup to the last dregs." Then he commits himself, trembling, into the ignoble hands of the executioner"

("The Rebel", Albert Camus)

Forty one years ago, on 22 July 1969, Franco decided that the royal Bourbon, Juan Carlos, will be the Successor, as Head of State, of his Terrorist and Genocidal Government.

Juan Carlos accept the request and, "receiving such Succession from His Excellency," said: "The political legitimacy that arose on July 18, was sworn in as Successor and the principles of the Movement" ( 'The Movement', the Franco's fascist political party)

In France, 217 years ago,

Luis Augusto Bourbon, Louis XVI,

was placed under the guillotine

by the power of the People's Assembly.

In Spain, in 1969,

a Regime of Terror

crown King Juan Carlos of Bourbon

as a Head of State...¡Post -generacionally- held for life!

THE MOST INSULTING MEDIEVAL SETBACK IN MODERN HISTORY

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The first debate over the fate of Louis XVI concerned whether the Convention could try the King at all, and if so, for what crimes. The Constitution of 1791 had promised Louis "inviolability," meaning immunity from prosecution. One of the first speakers was Louis–Antoine Léon de Saint–Just, a brilliant, idealistic, and young Jacobin deputy. He drew on Montesquieu as well as Rousseau to argue that the legislature indeed had both the political authority under the constitution and the moral justification to try the King.

"I shall undertake, citizens, to prove that the King can be judged...

I say that the King should be judged as an enemy and that even more than judge him, we must fight him. Also, in that he was not a party to the contract that unites all French people, the judicial procedure to follow is not to be found in Civil Law, but rather in Common Law.

Perhaps one day, men as far removed from our prejudices as we are from those of the Vandals will be astonished by the barbarity of an age in which the judging of a tyrant was thought to be something sacred. Where the people, having a tyrant to judge, raised him to the rank of citizen before investigating his crimes and were more concerned about what would be said about them than about the task at hand. And where a guilty man who belonged to the class of oppressors, the lowest class of humanity, became a martyr to their pride.

One day men will be astonished by the fact that humanity in the eighteenth century was less advanced than in the time of Caesar. Then a tyrant was slain in the midst of the Senate with no formalities but thirty blows of a dagger and with no other law save the liberty of Rome. And today we respectfully conduct a trial for a man who assassinated a people, caught in flagrante delicto, his murderous hands soaked with blood!

These same men who are to judge Louis also have a Republic to create. Those who attach any importance to the King receiving a fair punishment will never be able to create a Republic. For us, the sensitivity of our minds and character is a great obstacle to liberty. We make all error seem more attractive and, more often than not, truth for us is only the seduction of our tastes. . .

We must therefore courageously advance toward our goal, and if we desire a Republic, we must be serious about it. We judge ourselves severely, I would even say with rage. We think only of tempering the energy of the People and of liberty, whereas we hardly reproach our common enemy. And everyone, either from weakness or because they stand with the accused, look at each other before striking the first blow. We seek liberty, and we are becoming each other's slaves! We seek nature, and live armed, like wild savages. We desire a Republic, independence, and unity, but we are divided and treat a tyrant with gentleness . . .It would seem that we are searching for a law that would allow us to punish the King

The social contract is between citizens, not between citizens and government. A contract is useless against those who are not bound by it. Consequently, Louis, who was a party to it, cannot be judged by Civil Law. The contract was so oppressive that it bound the People, but not the King. Such a contract was necessarily void since nothing is legitimate that is not sanctioned by ethics and nature.

These reasons lead you all not to judge Louis as a citizen, but as a rebel. But besides these reasons, by what right does he demand to be judged by Civil Law, which is our obligation toward him, when it is clear that he himself betrayed the only obligation that he had undertaken towards us, that of our protection ? Is this not the last act of a tyrant, to demand to be judged by the laws that he destroyed? And Citizens, if we were to grant him a civil trial, in conformance with the laws and as a citizen, it would be him who would be trying us. He would be trying the People themselves.

For myself, I can see no middle ground. This man must reign or die. He will prove to you that all he has done, he has done to uphold his office with which he had been entrusted. By discussing this with him, you cannot make him incriminate himself for his hidden malice. He will lead you in a vicious circle created by your very accusations.

I will say more: a constitution accepted by a King did not bind the citizens. They had, even before his crime, the right to banish him and send him into exile. To judge a King as a citizen . . . that would astound a dispassionate posterity. To judge is to apply the law. A law is linked to justice, and common to mankind and kings? What does Louis have in common with the French people that they should treat him well after he betrayed them?

It is impossible to reign in innocence. The folly of that is all too evident. All Kings are rebels and usurpers. Do Kings themselves treat otherwise those who seek to usurp their authority? Was not Cromwell's memory brought to trial? And certainly Cromwell was no more usurper than Charles I. For when a people is so weak as to yield to the tyrant's yoke, domination is the right of the first comer, and it is no more sacred or legitimate for one than for another. These are the considerations that a generous and republican people must not forget when judging a King.

You will be told that the verdict is to be ratified by the People. If that is to be, why can they themselves not pass judgment? If we did not sense the weakness of such ideas, whatever form of government we might adopt would find us slaves. The sovereign would never be in his place, nor the magistrate in his, and the people would have no guarantee against oppression.

Citizens, the tribunal which must judge Louis is not a judiciary tribunal . . . it is a council . . . it is the People . . . it is you. And the laws that must guide us are those of citizens' rights. A civil trial would be unjust since the King, deemed to be a citizen, cannot be judged by the same men who have accused him. Louis is a foreigner among us. He was not a citizen before his crime: he could not vote, he could not bear arms. He is even less a citizen since his crime, and by what abuse of justice would you make him a citizen in order to condemn him? As soon as a man is found guilty, he leaves the polity, but quite to contrary, Louis would gain entry by his crime. I would go even farther . . . if you declare the King to be a citizen, he will slip from your grasp. Which of his obligations would you rely on in the current state of things?

I shall forever contend that the spirit in which the King will be judged is the same spirit with which the Republic will be established. The theory behind your verdict will be that of your public offices, and the measure of your philosophy in the verdict, will be the measure of your liberty in the constitution...

You will never see my personal will oppose the general will. I shall desire what the People of France, or the majority of its representatives, desire. But, as my personal will concerns a portion of the law which has not yet been written, I open myself to you in all frankness...

It is therefore you who must decide if Louis is the enemy of the French people, if he is an alien. If the majority of you decide to absolve him, then that verdict would have to be ratified by the People, for if no act of the sovereign can truly constrain a single citizen to pardon a King, even less could an act of the magistracy constrain the sovereign! . . ."

Source: M. J. Mavidal and M. E. Laurent, eds., Archives parlementaires de 1787 à 1860, première série (1787 à 1799), 2d ed., 82 vols. (Paris: Dupont, 1879–1913), 53–56:390–93; "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" © 2001 American Social History Productions, Inc.

......................................................................

Saint-Just's Second Speech on Louis XVI

By late December, the Convention was in the process of trying the King. Louis agreed to testify in his own defense. He justified the decisions of 1789–91 by pointing out that he had still been King and that he had consistently tried to rule within the parameters of the constitution. The next day, Saint–Just spoke for the second time, reproaching the deputies for allowing the proceedings to drag on during the war crisis. Finally he urged them to act decisively for liberty and against tyranny by condemning Louis.

"Any sensitive man on earth would respect our courage. What people ever made greater sacrifices for liberty! What people was more betrayed! What people less avenged! Let the King himself look into his heart and ask how he has treated this People who today are no more than just, no less than great?

Citizens, when first you deliberated the question of this trial, I told you that a king was outside the state, and by nature above the law. This is why whatever covenant may have been agreed upon between the People and the King (in this case an illegitimate covenant), it did not bind him. Nonetheless, you formed a tribunal, and the sovereign stands at the bar with the King who is before you pleading his case and defending himself.

You permitted that insult to the dignity of the people. Louis has cast the blame for his crimes on the ministers whom he oppressed and deceived. "Sire," wrote de Morgue to the King on 16 June 1792, "I hereby resign. The particular orders Your Majesty has given me prevent me from executing the laws." On another occasion, de Morgue tries to clear himself from having advised the King to approve the writ against fanatical priests. What sort of prince is it, before whom a minister needs to defend his integrity? And that man is supposed to be inviolable! Such is the circle in which you are placed: you are the judges, Louis the prosecutor, and the People the accused.

I do not know where this travesty of the most basic principles of justice will lead you. Had Louis refused your jurisdiction, the trap might not have been sprung. The denial of the sovereignty of the People would have been the final proof of his tyranny. But since the Revolution Louis has tended noticeably less towards open resistance. Supplely, seemingly unrefined and simplistic, he has shown his skill in dividing men. His unflagging policy was to remain motionless or to move in step with all patriots, just as today he seems even to work with his judges in order to make the insurrection appear to be but the rising of a lawless mob.

Defenders of the King, what would you require of us? If he is innocent, the nation is guilty. We must finish answering, for the very act of deliberating accuses the People.

I have heard talk of an appeal to the People of the verdict which the People itself will pronounce through us.

Citizens, if you permit an appeal to the People, you will be saying to them, "the guilt of your murderer is in doubt." Do you not see that such an appeal would tend to divide the People and the legislature, would tend to weaken representation, to restore monarchy, to destroy liberty? And if plotting succeeds in altering your verdict, I ask you gentlemen if you would be left with any option besides renouncing the Republic and returning the tyrant to his throne. There is but a small step from the King's exoneration to his triumph, and from there to the triumph of monarchy. Yet should the accusing people, the ravaged people, the oppressed people, be the judge? Did they not decline that responsibility after the tenth of August? Nobler, more scrupulous, less cruel than those who would send the accused before them, the People wanted a council to decide his fate. That tribunal has already shown too much weakness, and that weakness has already softened public opinion. If the tyrant appeals to his accusers, he does what Charles I never dared. In a functioning monarchy, it is not you who judge the King, for you are nothing by yourselves, but the People judge and speak through you.

Today will decide the fate of the Republic. It is doomed if the tyrant goes unpunished. The enemies of the common good will reappear, meet, and hope. The forces of tyranny will pick up their pieces like a reptile renewing its lost tail. All evil men are for the King. Who here then can join him? False pity is on the lips of some, anger on the lips of others. Everything serves to either corrupt us or frighten us down to our souls. Be steadfast in your severity and rest assured of the People's gratitude in time to come. Be more attuned to the true interests of the People than to the empty concerns and empty clamor by which the schemers seek to play upon the respect you have for the rights of the People, the better to destroy those rights and deceive the People.

You called for war on all the tyrants of the world, and you would respect your own! Are bloody laws enforced only against the oppressed, and is the oppressor to be spared? . . .

We have shown an odd scorn towards the principles and character of this situation. Louis wishes to be King, to speak as King even while denying it. But a man unjustly placed above the law can present the judge only with his innocence or his guilt. Louis can only challenge us by proving his innocence and innocence has no need to challenge its judges for it has nothing to fear. Let Louis explain how the papers you have seen may favor liberty, let him show his wounds, and let us judge the People.

Some will say that the Revolution is over, that we have nothing more to fear from the tyrant, and that the law now calls for the death of a usurper. But, citizens, tyranny is like a reed which bends with the wind and which rises again. What do you call a Revolution? The fall of a throne, a few blows levied at a few abuses? Moral order is like physical order: abuses disappear for an instant, just as the morning dew dries, and then just as it falls again with the night, so the abuses reappear. The Revolution begins when the tyrant ends.

I have attempted to show the conduct of the King. It is now for you to be just. You must put aside all considerations but those of justice and the common good. Above all, you must not compromise your liberty which was acquired at so high a price. You must pronounce a verdict which allows for no appeal. If you do not, the greatest of criminals, and a King, will have been the first to enjoy a right refused to citizens, and the tyrant will once again be above the law, even after his trial. Nor should you permit the verdict to be challenged, for it reflects the wishes and opinions of all. If those who spoke of the King are challenged, we will challenge, in the name of France, those who said nothing for our country or those who deceived it.

France is amongst us; let each man choose between her and the King, between the exercise of justice by the People and the exercise of your own weaknesses.

Weigh, if you will, the example which you owe the world, the impetus you owe liberty and the unflagging justice you owe the People, against criminal pity for one who never felt such a sentiment. Say to Europe as it bears witness: Unite your kings against us for we have rebelled against kings. Have the courage to speak the truth, for it seems to me that there are those here who fear sincerity. Truth burns silently in all hearts, like a lamp burning over a tomb. Yet if there be someone among you unconcerned by the fate of the Republic, let him fall at the feet of the tyrant, let him return the knife with which he slaughtered your fellow citizens, let him forget all crimes of the King and tell the people that we have been corrupted, and that we have been less interested in their well-being than in the fate of an assassin"

Source: M. J. Mavidal and M. E. Laurent, eds., Archives parlementaires de 1787 à 1860, première série (1787 à 1799), 2d ed., 82 vols. (Paris: Dupont, 1879–1913), 53–56:706–10; "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" © 2001 American Social History Productions, Inc.