THE ESSENTIAL

FRANKFURT SCHOOL READER

Edited by Andrew Arata & Eike Gebhardt

Introduction by Paul Piccone

CONTINUUM . NEW YORK

While Marcuse's early essays on dialectic bristle with phenomenological categories (he had been an assistant to Heidegger), they already embody the crucial shift from ontology to history, from Being to concrete being-in-the-world, as Adorno remarked with cautious praise in a contemporary review. The essay reproduced here, written in 1960 as a new preface to his Reason and Revolution, retains few traces of this heritage.

Marcuse's condensed expose shows that dialectic, in the Hegelian sense used by the critical theorists, is neither an abstract method nor an ideology. An important feature of the essay is the relation Marcuse establishes to the esthetic mode (more systematically and historically grounded in Eros and Civilization) as an alternative of non-instrumental perception and thus an aspect of autonomous reason. This essay goes a long way to explain the interdisciplinary orientation of many of the older Frankjurtians.

Paul Piccone

...............................

This book was written in the hope that it would make a small contribution to the revival, not of Hegel, but of a mental faculty which is in danger of being obliterated: the power of negative thinking. As Hegel defines it: "Thinking is, indeed, essentially the negation of thatwhich is immediately before us." What does he mean by "negation," the central category of dialectic?

Even Hegel's most abstract and metaphysical concepts are saturated with experience of a world in which the unreasonable becomes reasonable and, as such, determines the facts; in which unfreedorn is the condition of freedom, and war the guarantor of peace.

This world contradicts itself. Common sense and science purge themselves from this contradiction; but philosophical thought begins with the recognition that the facts do not correspond to the concepts imposed by common sense and scientific reason-in short, with the refusal to accept them. To the extent that these concepts disregard the fatal contradictions which make up reality, they abstract from the very process of reality.

The negation which dialectic applies to them is not only a critique of a conformistic logic, which denies the reality of contradictions; it is also a critique of the given state of affairs on its own grounds of the established systemof life, which denies its own promises and potentialities.

Today, this dialectical mode of thought is alien to the whole established universe of discourse and action.

It seems to belong to the past and to be rebutted by the achievements of technological civilization. The established reality seems promising and productive enough to repel or absorb all alternatives.

Thus acceptance and even affirmation of this reality appears to be the only reasonable methodological principle. Moreover, it precludes neither criticism nor change; on the contrary, insistence on the dynamic character of the status quo, on its constant "revolutions," is one of the strongest props for this attitude. Yet this dynamic seems to operate endlessly within the same framework of life: streamlining rather than abolishing the domination of man, both by man and by the products of his labor. Progress becomes quantitative and tends to delay indefinitely the turn from quantity to quality-that is, the emergence of new modes of existence with new forms of reason and freedom.

The power of thinking is the driving power of dialectical thought, used as a tool for analyzing the world of facts in terms of its internal inadequacy.

I choose this vague and unscientific formulation in order to sharpen the contrast between dialectical and undialectical thinking.

"Inadequacy" implies a value judgment. Dialectical thought invalidates the a priori opposition of value and fact by understanding all facts as stages of a singel process, a process which subject and object are so joined that truth can be determined only within the subject-object totality. All facts embody the knower as well as the doer; they continuously translate the past into the present. The objects thus "contain" subjectivity in their very structure.

Ahora bien, ¿qué -o quíen- es esta subjetividad (esta epistemologia) en un sentido literal que constituye el mundo objetivo? Hegel responde con una serie de términos que denotan al sujeto en sus varias manifestaciones: Pensamiento, Razon, Espiritu, Idea. Desde el momento que no tenemos un -fluyente- acceso a esos conceptos a los cuales los siglos XVIII y XIX aún tenian, yo intentaría esquematizar las concepciones hegelianas en términos más familiares:

Nada es "real" que no sostenga en sí mismo su existencia sobre una lucha vida-muerte bajo las situaciones y condiciones de su existencia.

Ello puede ser una lucha ciega o aún inconsciente como la de la materia inorganica, pero ello tambien puede ser consciente y concertado como la lucha de la humanidad bajo sus propias condiciones y las de la naturaleza. La "realidad" es la constante renovación que resulta del proceso de la existencia, proceso consciente o inconsciente en el cual "that which is" se convierte en "other than itself", y la identidad --en esta renovacion-- solo es la continua negación de la existencia inadecuada, alienada, donde el sujeto se mantiene a si mismo en "being other than itself"

Por consiguiente, cada realidad es una "realización", un desarrollo de una "subjetividad", esta última "come to itself" en la historia donde el desarrollo -de la misma- tiene un contenido racional. Hegel lo define como "el progreso de la conciencia de libertad"

Otra vez aparece aqui un juicio de valor y esta vez impuesto en el mundo como un todo. Pero la libertad es para Hegel una categoria ontologica: es decir, el no ser un mero objeto, el ser el sujeto de su propia existencia que no sucumbe a las condiciones de su existencia sino que transforma factualmente su realización. Esta transformacion es, segun Hegel, la energía de "nature and history, the inner structure of all being" Uno podría desdeñar esta idea, pero debemos ser consciente de sus importantes implicaciones.

El pensamiento dialéctico (y no el epistemológico) empieza con la experiencia de que el mundo es "unfree", es decir, "man and nature" existen en condiciones de alienación, existen "diferentes de lo que son" -"other than they are"-. Y cualquier modo de pensamiento que excluya esta contradicción de su lógica es "a fault logic".

El pensamiento sólo "corresponde" con la realidad cuando transforma la realidad en la comprensión de su contradicctoria estructura.

Aqui el principio dialectico conduce su pensamiento mas alla de los límites de la filosofia epistemológica porque comprender la realidad significa entender lo que realmente son las cosas, y esto, a su vez, significa rechazar su mera factualidad. Rechazar constituye el proceso del pensamiento tambien como el de su accion. Mientras el que el metodo cientifico lleva desde la inmediata experiencia de las cosas a su matematica-logica estructura, el pensamiento filosófico conduce desde la inmediata experiencia de la existencia a su estructura historica: el principio de la libertad.

La libertad es la intrinseca dinámica de la existencia, y el genuino proceso de la existencia en un mundo "unfree" es "la continua negación de lo que amenaza negar la libertad". Thus freedom is essentially negative: existence is both alienation and the process by which the subject comes to itself in comprehending and mastering alienation.

For the history of mankind, this means attainment of a "state of the world" in which the individual persists in inseparable harmony with the whole, and in which the conditions and relations of his world "possess no essential objectivity independent of the individual".

As to the prospect of attaining such a state, Hegel was pessimistic: the element of reconciliation with the established state of affairs, so strong in his work, seems to a great extent due to this pessimism or, if one prefers, this realism. Freedom is relegated to the realm of pure thought, to the Absolute Idea. Idealism by default: Hegel shares this fate-with the main philosophical tradition.

Dialectical thought thus becomes negative in itself. Its function is to break down the self-assurance and self-contentment of common sense, to undermine the sinister confidence in the power and language of facts, to demonstrate that unfreedom is much at the core of things that the development of their internal contradictions leads necessarily to qualitative change: the explosion and catastrophe of the established state of affairs.

Hegel sees the task of knowledge as that of recognizing the world as Reason by understanding all objects of thought as elements and aspects of a totality which becomes a conscious world in the history of mankind. Dialectical analysis ultimately tends to become historical analysis, in which nature itself appears as part and stage in its own history and in the history of man. The progress of cognition from common sense to knowledge arrives at a world which is negative in its very structure because that which is real opposes and denies the potentialities inherent in itself, potentialities which themselves strive for realization. Reason is the negation of the negative.

Interpretation of that-which-is in terms of that-which-is-not, confrontation of the given facts with that which they exclude this has been the concern of philosophy wherever philosophy was more than a matter of ideological justification or mental exercise.

The liberating function of negation in philosophical thought depends upon the recognition that the negation is a positive act: that-which-is repels that-which-is-not and, in doing so, repels its own real possibilities.

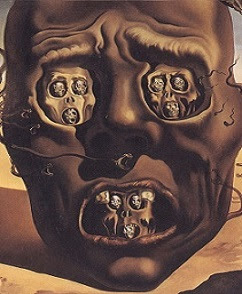

Consequently, to express and define that-which-is on its own terms is to distort and falsify reality, because Reality is other and more than that codified in the logic and language of facts. Here is the inner link between dialectical thought and the effort of avant-garde literature: the effort to break the power of facts over the word, and to speak a language which is not the language of those who establish, enforce and benefit from the facts.

Como el poder de los hechos dados tiende a convertirse en totalitarios para absorver:

Pag. 449

secours de ce qui n' existe pas?">(What are we without the help ofthat which does not exist?) This is not "existentialism. It is something more vital andmore desperate: the effort to contradict a reality in which all logic and all speech are false to the extent that they are part of a mutilated whole

. The vocabulary and grammar of the language of contradiction are still those of the game (there are no others), but the concepts codified in the language of the games are redefined by relating them to their "determinate negation". This term, which denotes the governing principle of dialectical thought, can be explained only in a textual interpretation of Hegel's Logic. Here it must suffice to emphasize that, by virtue of this principle, the dialectical contradiction is distinguished from all pseudo- and crackpot opposition, beatnik and hipsterisrn. The negation is-determinate if it refers the established state of affairs to the basic factors and forces which make for its destructiveness, as well as for the possible alternatives beyond the status quo.

In the human reality, they are historical factors and forces, and the determinate negation is ultimately a political negation. As such, it may well find authentic expression in nonpolitical language, and the more so as the entire dimension of politics becomes an integral part of the status quo. Dialectical logic is critical logic: it reveals modes and contents of thought which transcend the codified pattern of use and validation. Dialectical thought does not invent these contents; they have accrued to the notions in the long tradition of thought and action. Dialectical analysis merely assembles and reactivates them; it recovers tabooed meanings and thus appears almost as a return, or rather a conscious liberation, of the repressed!

Since the established universe of discourse is that of an unfree world, dialectical thought is necessarily destructive, and whatever liberation it may bring is a liberation in thought, in theory.

However, the divorce of thought from action, of theory from practice,is itself part of the unfree world. No thought and no theory can undo it; but theory may help to prepare the ground for their possible reunion, and the ability of thought to develop a logic and language of contradiction is a prerequisite for this task.

In what, then, lies the power of negative thinking? Dialectical thought has not hindered Hegel from developing his philosophy into a neat and comprehensive system which, in the end, accentuates the positive emphatically.

I believe it is the idea of Reason itself which is the undialectical element in Hegel's philosophy This idea of Reason comprehends everything and ultimately absolves everything, because it has its place and function in the whole, and the whole is beyond good

Pag. 450

Pag. 451

testify to an awareness of the radical falsity ofthe established forms of life is faulty thinking.

Abstraction from this all-pervasive condition is not merely immoral; it is false. For reality has become technological reality, and the subject is now joined with the object so closely that the notion of object necessarily includes the subject.

Abstraction from their interrelation no longer leads to a more genuine reality but to deception, because even in this sphere the subject itselfis apparently a constitutive part of the object as scientifically determined.

The observing, measuring, calculating subject of scientific method, and the subject of the daily business of life-both are expressions ofthe same subjectivity: man. One did not have to wait for Hiroshima in order to have one's eyes opened to this identity.

And as always before, the subject that has conquered matter suffers under the dead weight of his conquest. Those who enforce and direct this conquest have used it to create a world in which the increasing comforts of life and the Ubiquitous power of the productive apparatus keep man enslaved to the prevailing state of affairs.

Those social groups which dialectical theory identified as the forces of negation are either defeated or reconciled with the established system. Before the power of the given facts, the power of negative thinking stands condemned.

This power of facts is an oppressive power; it is the powerof man over man, appearing as objective and rational condition. Against this appearance, thought continues to protest in the name of truth. And in the name of fact: for it is the supreme and universal fact that the status quo perpetuates itself through the constant threat of atomic destruction, through the unprecedented waste of resources, through mental impoverishment, and-last but not least-e-through brute force.

These are the unresolved contradictions. They define every single fact and every single event; they permeate the entire universe of discourse and action.

Thus they define also the logic of things: that is, the mode of thought capable of piercing the ideology and of comprehending reality whole.

No method can claim a monopoly of cognition, but no method seems authentic which does not recognize that these two propositions are meaningful descriptions of our situation: