This Face Changes the Human Story. But How?

"The Rosetta stone” to the origins of Homo".

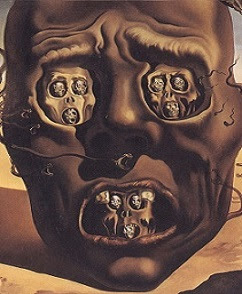

“It’s an animal that appears to have had the cognitive ability to recognize its separation from nature,”

Extractos del artículo:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/09/150910-human-evolution-change/

"But then there was the head. Four partial skulls had been found—two were likely male, two female. In their general morphology they clearly looked advanced enough to be called Homo.

But the braincases were tiny—a mere 560 cubic centimeters for the males and 465 for the females, far less than H. erectus’s average of 900 cubic centimeters, and well under half the size of our own.

A large brain is the sine qua non of humanness, the hallmark of a species that has evolved to live by its wits. These were not human beings. These were pinheads, with some humanlike body parts.

“The message we’re getting is of an animal right on the cusp of the transition from Australopithecus to Homo,” Berger said as the workshop began to wind down in early June. (2015)

“Everything that is touching the world in a critical way is like us. The other parts retain bits of their primitive past.”

In some ways the new hominin from Rising Star was even closer to modern humans than Homo erectus is.

To Berger and his team, it clearly belonged in the Homo genus, but it was unlike any other member.

They had no choice but to name a new species. They called it Homo naledi (pronounced na-LED-ee), tipping a hat to the cave where the bones had been found: In the local Sotho language, naledi means “star.”

That made for a mystery as perplexing as that of H. naledi’s identity: How did the remains get into such an absurdly remote chamber? Clearly the individuals weren’t living in the cave; there were no stone tools or remains of meals to suggest such occupation.

Conceivably a group of H. naledi could have wandered into the cave one time and somehow got trapped—but the distribution of the bones seemed to indicate that they had been deposited over a long time, perhaps centuries.

If carnivores had dragged hominin prey into the cave, they would have left tooth marks on the bones, and there weren’t any. And finally, if the bones had been washed into the cave by flowing water, it would have carried stones and other rubble there too. But there is no rubble—only fine sediment that had weathered off the walls of the cave or sifted through tiny cracks.

Having exhausted all other explanations, Berger and his team were stuck with the improbable conclusión that bodies of H. naledi were deliberately put there, by other H. naledi.

Until now only Homo sapiens, and possibly some archaic humans such as the Neanderthals, are known to have treated their dead in such a ritualized manner.

The researchers don’t argue that these much more primitive hominins navigated Superman’s Crawl and the harrowing shark-mouth chute while dragging corpses behind them—that would go beyond improbable to incredible.

Maybe back then Superman’s Crawl was wide enough to be walkable, and maybe the hominins simply dropped their burden into the chute without climbing down themselves. Over time the growing pile of bones might have slowly tumbled into the neighboring chamber.

Disposal of the dead brings closure for the living, confers respect on the departed, or abets their transition to the next life. Such sentiments are a hallmark of humanity. But H. naledi, Berger emphatically stresses, was not human—which makes the behavior all the more intriguing.

“It’s an animal that appears to have had the cognitive ability to recognize its separation from nature,” he said.

Though such advanced behavior is unknown in other primitive hominins, “there appears to be no other option for why the bones are there,” says lead scientist Lee Berger.

H. naledi was much closer in appearence to Homo species such as H. erectus than to australopithecines, such as Lucy. But it possesses enough traits shared with no other member of our genus that it warrants a new species name.

The mysteries of what H. naledi is, and how its bones got into the cave, are inextricably knotted with the question of how old those bones are—and for the moment no one knows. In East Africa, fossils can be accurately dated when they are found above or below layers of volcanic ash, whose age can be measured from the clocklike decay of radioactive elements in the ash.

At Malapa, Berger had gotten lucky: The A. sediba bones lay between two flowstones—thin layers of calcite deposited by running water—that could also be dated radiometrically. But the bones in the Rising Star chamber were just lying on the cave floor or buried in shallow, mixed sediments. When they got into the cave is an even more intractable problem to solve than how.

Most of the workshop scientists fretted over how their analysis would be received without a date attached. (As it turned out, the lack of a date would prove to be one impediment to a quick publication of the scientific papers describing the finds.) But Berger wasn’t bothered one bit. If H. naledi eventually proved to be as old as its morphology suggested, then he had quite possibly found the root of the Homo family tree.

But if the new species turned out to be much younger, the repercussions could be equally profound. It could mean that while our own species was evolving, a separate, small-brained, more primitive-looking Homo was loose on the landscape, as recently as anyone dared to contemplate.

As the exhilarating workshop came to an end with that fundamental question still unresolved, Berger was sanguine as always. “No matter what the age, it will have tremendous impact,” he said, shrugging.

A fully modern hand sported wackily curved fingers, fit for a creature climbing trees. The shoulders were apish too, and the widely flaring blades of the pelvis were as primitive as Lucy’s—but the bottom of the same pelvis looked like a modern human’s. The leg bones started out shaped like an australopithecine’s but gathered modernity as they descended toward the ground. The feet were virtually indistinguishable from our own.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

La mano es el espejo de alma.

El espejo de nuestro trabajo. El espejo de nosotros mismos.

En "Dialectics of Nature", dice Engels: 'el trabajo creó al hombre mismo'. En ésta mano está reflejada ésta antropogénesis. Aquel tópico eslabón perdido del que tanto se ha hablado. Es una mano que sigue sirviendo para subirse a los árboles y, al mismo tiempo, las palmas de la mano, la muñeca y el pulgar son humanoides lo que denota que construían herramientas.

El ser de ésta mano, como dice Berger, --el director de este grandioso descubrimiento-- es un criatura que parece que tenía la habilidad cognoscitiva para reconocer su separación de la Naturaleza, lo que significa la aparición de de la conciencia.

Esta ha debido ser una de las muchísimas ramas evolutivas del Homo con conciencia que se desarrollaron en la Naturaleza, unas no tuvieron éxito en su evolución y se extinguieron, otras fueron aniquiladas o comidas por otras, y siguiendo la conclusión de Oscar Kiss en su conocida monografía, nosotros descendemos de una de éstas ultimas.

Pero lo mas misterioso para nosotros es la relación existente entre sentirse separado, arrojado de la Naturaleza, y la conciencia de ello.

Y que cuando se logra alcanzar conciencia dentro de la Naturaleza (proceso evolutivo muchísimo mas largo que lo que se logra con la evolución artificial porque ningún elemento exógeno la acelera), sin estar separado de ella, es la evolución natural, en la cual están incluidas todas las demás criaturas que comparten con nosotros el planeta...excepto nosotros, claro.

El nacimiento de la muerte

Y el nacimiento de enterrar la muerte

en el comienzo de una sui generis especie

de impredecible desarrollo evolutivo.